This article is part of the 2018 NMJ Oncology Special Issue. Download the full issue here.

Abstract

Cancer alters almost every aspect of patients’ and caregivers’ lives, including their sexuality. Many factors during cancer treatment can impact sexual desire, including sequelae of treatments, fatigue, hormonal changes, and pain. Patients look to their healthcare providers to start the conversation about sexuality, and many never receive information about how cancer treatments may alter their sexuality. Sexual intimacy includes much more than intercourse. Providers can help patients and their partners expand their understanding of intimacy and sexuality to include all aspects of sensuality. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients and their partners require appropriate support, both during and after cancer treatment. Sexuality has a place in end-of-life care and can profoundly enhance a patient and their partner’s last phase of their life together. Vaginal dryness, one of the most commonly reported sexual concerns for women, can be addressed with nonhormonal treatments. For men, difficulty achieving and maintaining an erection is one of the most widely reported sexual concerns. Conventional treatments for erectile dysfunction (ED) include phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor therapy; constriction devices, intraurethral prostaglandins, and penile injection therapy; and penile prosthesis implantation. Combining these therapies often yields better outcomes for cancer patients. Naturopathic and other vitalistic medicines offer tools to restore core energy, which in turn can enhance libido, intimacy, and sexuality.

Introduction

Over 15.5 million people in the United States have a history of cancer,1 and an estimated 60% of these cancer survivors report having sexual difficulties. Despite these astonishing figures, less than 20% of survivors seek a healthcare provider’s help for intimacy problems that result from their cancer treatment.2

Many cancer patients are unaware of how cancer treatments will impact their sexuality, and a minority of oncologists are willing to broach the subject. An Italian study of breast cancer survivors, for example, reported that 60% of postmenopausal and 39.4% of premenopausal breast cancer survivors developed vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) as a result of cancer treatment. Despite this high rate of VVA, only 48% of breast cancer oncologists surveyed discussed the potential for vulvovaginal changes with their patients before the onset of treatment.3 Forty-one percent of the oncologists referred patients to a gynecologist for VVA treatment and 35.1% managed VVA on their own; 25% of the patients were unaccounted for.

Context for sexuality: the life cycle of a relationship

Dr. Patricia Love, in her book Hot Monogamy, clarifies why libido usually changes dramatically over the course of a relationship by identifying 3 distinct stages:4

- Stage 1: During the first 6 months after falling in love, the body produces prodigious amounts of energizing, pleasure-producing hormones, including phenylethylamine, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Every thought about a partner, every touch, every interaction triggers a “dump” of these bliss-producing hormones. During this early stage, people will do all kinds of things they normally would not do in order to be with their new partner and experience this hormonal rush.

- Stage 2: The production of the bliss-producing hormones declines over the next 18 to 24 months.

- Stage 3: By 24 to 30 months, hormone levels return to normal range. At that point you hope you like your partner because the hormonal ride is over.

According to the American Cancer Society, 9 out of 10 cancer patients are diagnosed after age 50;5 therefore, many cancer patients are in already established, long-term relationships, often well beyond the initial high-libido period.

Why does libido decline?

Any individual may experience decline of libido, for one or more of the following reasons:

- Decline of initial hormonal surge (see above)

- Menopause

- Andropause

- Emotional distress

- Changes in cardiovascular function (affects the entire vascular system, including the genital region)

- Fatigue

Cancer patients face particular challenges that may lead to loss of libido:

- Cancer-related fatigue

- Changes after surgery (eg, scar tissue formation, loss of tissue elasticity, pain)

- Vaginal changes due to chemotherapy and/or radiation

- Erectile dysfunction (ED)

- Painful bone metastases

- Loss of tissue elasticity from radiation

- Changes in body image

Although patients with pelvic tumors and reproductive cancers (cancers of the cervix, ovaries, uterus, vagina, vulva, breast, prostate, testicles, and epididymis) are at highest risk of developing sexual dysfunction, all cancer patients have increased tendency for issues with intimacy.

Research in Britain revealed both men and women have reduced sexual frequency, sexual satisfaction, and engagement for both penetrative and nonpenetrative sexual activities after cancer treatment. These changes were true for reproductive and nonreproductive cancer types. Cancer survivors’ primary concerns included the physical consequences of cancer treatment; psychological factors; body image; and relationship factors. For women, the most commonly reported sexual difficulties included vaginal dryness, fatigue, and feeling unattractive. Men cited ED, the effects of surgery, and aging as most problematic. Conversely, several participants reported experiencing increased intimacy and closeness after cancer treatment.6

Sexuality: beyond intercourse

Male sexuality in our culture often is narrowed, even telescoped, to encompass only “erection” and “performance,” that is, the ability to sustain an erection and ejaculate. Survivors of prostate cancer often struggle with this limited understanding of sexuality, particularly if their cancer treatment alters or eliminates their ability to have an erection. Cancer impacts multiple physical and psychosocial domains, and ideally these patients would be viewed as a whole person within the context of a “biopsychosocial model” that includes their partner as a complex whole.7

One of the primary ways clinicians can support cancer survivors is to help them expand their understanding of sexuality to include sensuality. As a sexual signature, sensuality is the ability to fully experience one’s senses. Smelling, tasting, seeing, hearing, touching, and feeling combine to awaken the body and can strongly contribute to a sexual connection. Masters and Johnson’s book Heterosexuality includes a chapter, “Sex and Sensuality,” that outlines progressive exercises to cultivate sensuality in a sexual relationship. These exercises can easily be adapted to LGBTQ relationships as well. Cultivating sensuality in a relationship requires communication as each partner has his or her own particular comfort level for sensory stimulation.8

The impact of cancer treatment on caregivers

Many caregivers struggle with the impact of cancer treatments on their partners.9 Of 156 caregivers responding to a survey, 76% of partners with nonreproductive cancer types and 84% of those with reproductive cancers reported changes in their sexual relationship. Seventy-nine percent of male and 59% of female caregivers reported reduction or cessation of sexual activity. Despite these changes, only 14% of men and 19% of women discussed and renegotiated these changes with their partners.

Caregivers offered several reasons for these adjustments including the impact of cancer treatments; exhaustion from their caregiving role; and redefining their mate as a patient, not a sexual partner. Caregivers associated sexual changes with self-blame, rejection, sadness, anger, and lack of sexual fulfillment. Ideally, all healthcare providers would acknowledge the sexual needs of people with cancer as well as their partners during cancer treatment and palliative care.

Sexuality and Cancer Among the LGBTQ Community

The current medical system primarily is oriented to serve heterosexual patients. In the United States, however, a significant portion of the population identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer. Because this group has been closeted, or, in truth, “hidden in plain sight,” for generations, the special needs and concerns of this population have been largely overlooked. Approximately 3% to 12% of adults in the United States identify as LGBTQ,10 and 0.6% of the US population identify as transgender.11

Definitions

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual are defined by sexual orientation or sexual attraction. Those who identify as transgender relate to a gender that does not align with their sex assigned at birth.12 Queer or “questioning” identify as sexual and/or gender minorities but do not specifically identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender. Queer also refers to people who are currently exploring their sexual orientation or gender identity.13,14

Special concerns and healthcare needs of the LGBTQ community

The LGBTQ community, also referred to as sexual and gender minorities (SGMs), is a medically underserved and understudied population in the United States.10 This population faces several barriers to healthcare, such as difficulty obtaining and/or affording health insurance coverage, fear of judgment and/or stigmatization by healthcare providers, and healthcare providers’ lack of knowledge about LGBTQ-specific health issues.15

One in 5 transgender patients seeking healthcare is turned away by providers,16-18 and LGBTQ people are at increased risk for depression, anxiety, suicide, and substance abuse. Lesbian and bisexual women are more likely to be obese than straight women,19-22 which in turn increases their risk for developing cancer.

Sexual minorities overall have increased incidences and mortality rates for several types of cancer, including the following:

- Lung

- Colorectal

- Anal

- Prostate

- Cervical

- Breast14-22

Many physicians incorrectly assume that because lesbian women do not have intercourse with men, they are at lower risk for contracting human papilloma virus (HPV) and therefore at lower risk of developing cervical and other reproductive cancers. Data demonstrates just the opposite: bisexual women have the highest rates of any type of cancer (17.6%), followed by lesbian women (14%) and heterosexual women (11.9%). Researchers suggest many possible contributing factors, including bisexual women passing HPV exposures from male to female partners; increased obesity rates in lesbian and bisexual women; and greater prevalence of high-risk health behaviors in the LGBTQ community, such as alcohol abuse and cigarette smoking.23

Sexuality During End-of-Life Care

For each patient, dying “is a process of personal trial and error.”24 Each patient must discover through his or her own experience what matters most during this final stage of life. Sexuality may or may not play an important role in a patient’s end-of-life journey. For many older patients, sexuality may have shifted to nongenital sensuality. These patients and their partners tend to fit more easily into social and institutional norms, such as inpatient hospital and hospice environments.25

Younger patients may struggle with grief and anger over the loss of their sexual relationship. Patients both young and old may desire intimate connection in the most life-affirming way possible during this vulnerable time. They may want to touch and be touched, and they may require more privacy.26,27

Physician and medical sex therapist Dr. Margaret Redelman notes, “It is the health professional's responsibility to raise this issue.”28 Ideally healthcare providers would advocate for patients to have the privacy and support they need for intimacy during end-of-life care.

Benefits of sexuality in end-of-life care

- Improves self-concept and sense of personal integrity29

- Decreases hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity, which in turn modulates the autonomic nervous system30,31

- Triggers oxytocin release in men and women,32 which acts on the emotional centers of the brain, generally leading to comforting feelings of warmth and relaxation33

- Increases oxytocin, which acts as a natural anti-stress neurotransmitter34

- Improves sleep quality35 and may have a sedative effect36

- Increases pain thresholds, specifically via vaginal self-stimulation that can produce analgesia rather than anesthesia37-40

Sexual Challenges For Women After Cancer Treatment

Talking about sexuality with women

In a cross-sectional survey of 218 women with a history of breast or gynecological cancer, 70% (n=152) reported they preferred that the medical team raise the topic of sexual health needs; 48% (n=105) raised the topic themselves. Most (66%; n=144) preferred written educational material followed by discussion with their healthcare provider. Younger women preferred to discuss their concerns face-to-face. Older women were less interested in online interventions, despite 94% having computer access.41

Healthcare providers can support women by broaching the topic, offering written information, and scheduling time to discuss concerns and review treatment suggestions.

Breast cancer treatment and sexuality

Recent research demonstrates that the more invasive a woman’s breast cancer surgery, the more likely she is to have sexual dysfunction after treatment. In one study, 34% of 74 breast surgery patients reported having sexual dysfunction after surgery.¹ Of the women who had conservative mastectomy, however, only 14% reported having sexual dysfunction. Of women who had a radical mastectomy plus reconstruction, 29% reported having sexual difficulties, while 63% of those who had radical mastectomy without reconstruction reported having sexual dysfunction. The women who had mastectomy without reconstruction tended to be older. Age and changes in self-image in addition to the invasiveness of their surgery may have contributed to the significantly higher rate of sexual dysfunction among this group of patients.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM)

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) affects approximately 50% of postmenopausal women.42-44 Genitourinary syndrome of menopause is characterized by the involution of genitourinary mucosa and the adjacent vulvo-vaginal tissues, and a reduction in both the quantity of elastic fibers and the vascularization of genitourinary tissue.45 As a result, the vaginal diameter contracts and the vaginal epithelium becomes susceptible to infection. The clinical presentation may include dryness, burning sensation, severe dyspareunia, dysuria, and stress urinary incontinence.46,47 Many women face this problem for more than one-third of their adult life,45 making it an important issue to address.

One of the primary ways clinicians can support cancer survivors is to help them expand their understanding of sexuality to include sensuality.

According to research conducted in 2012 as part of the National Survey of Sexual Health Behavior, 30% of women over age 18 report pain during vaginal sex, 72% report pain during anal sex, and "large proportions" don't tell their partners when sex is painful.48 Debra Herbenick, PhD, a professor at the Indiana University School of Public Health and one of the researchers behind the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior notes, “when it comes to ‘good sex,’ women often mean without pain, men often mean they had orgasms.”49

Addressing vulvovaginal atrophy

Vaginal dryness is the most commonly reported symptom women experience after gynecological cancer treatment. Most oncologists (71%) prefer nonhormonal treatments because of the fear of increased cancer recurrence, possible interference with tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, and fear of litigation.3 The following are the primary nonsurgical means of rejuvenating vulvovaginal tissue:

- Lubricants

- Hormones

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser

- Radiofrequency devices

Lubricants

For cancer patients, the first-line therapy for vaginal dryness is regular applications of water-based gels and vaginal moisturizers to hydrate the vaginal wall.50,51 Vaginal moisturizers are similar to vaginal lubricants but stay in contact longer with the vaginal wall, thereby heightening their lubricating effects. Vaginal moisturizers may have similar efficacy to topical vaginal estrogen and ideally would be offered to women who choose to avoid hormone therapy.52

One research study compared the efficacy of vitamin E suppositories to 0.625 mg of conjugated estrogen cream applied nightly for 2 weeks, then twice a week for another 10 weeks. The study measured “success” as an increase in the vaginal maturation value of at least 10 units. Seventy-six percent of the vitamin E group and 100% of the conjugated estrogen group successfully reached this benchmark.53

Another study compared hyaluronic acid gel with estriol cream for vaginal dryness. Both groups reported a similar improvement in vaginal lubrication; however, the estriol group had a decrease in vaginal pH and the hyaluronic acid group did not.54

The OVERcome trial (n=25) incorporated olive oil, vaginal exercise and moisturizer to address vaginal dryness. The women performed pelvic floor muscle relaxation exercises twice a day to manage pelvic floor muscle tension. They also applied a polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer 3 times a week to alleviate vaginal dryness, used olive oil as a lubricant during intercourse, and completed a weekly compliance diary. The women rated pelvic floor muscle relaxation exercises (92%), vaginal moisturizer (88%), and olive oil (73%) as helpful. Researchers also reported an unexpected finding—6 of the women (11%) had vaginal stenosis.55

Many patients who are diagnosed with vaginal stenosis are incorrectly told they can never regain normal vaginal elasticity. With patience and gradual stretching, women can restore normal vaginal elasticity. Vaginal dilators can be used for this purpose, as can a finger gently inserted into the vagina. Over time the woman uses a larger diameter dilator or inserts a larger finger, or more than 1 finger. Gentle, gradual stretching over time is the key to success.

Choosing an appropriate vaginal lubricant

Vaginal lubricants vary widely in osmolality and pH. Normal vaginal pH ranges from 3.8 to 4.5. Vaginal pH commonly becomes more alkaline after menopause, which can increase the tendency for vaginal and urinary tract infections. Ideally, a vaginal lubricant for a menopausal woman would be slightly acidic and have an appropriate osmolality. Some water-based lubricants are hyperosmolar, which dehydrates the vaginal cells and increases susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections. This is most commonly caused by glycerin, so women should avoid water-based lubricants that list glycerin among the top 3 ingredients.

Edwards and Panay compiled an excellent international review of lubricant and moisturizer products that summarizes ingredients, pH, and osmolality. This is a valuable guide to choosing the correct products for a particular patient (eg, “sperm friendly,” anal, vaginal lubricants).56

The author’s clinical experience is that calendula suppositories improve vaginal dryness, but there is no data to support this in clinical practice. Coconut or olive oil on a nightly basis may also be helpful. The key to success is using a lubricant nightly, regardless of whether the patient engages in penetrative sexual activity or not.

Topical vaginal hormones for cancer survivors

While the majority of oncologists avoid prescribing hormones for survivors of reproductive cancer, recent research suggests that certain hormones in extremely low doses may be viable for addressing VVA. While I personally am uncomfortable with this option, I offer this information as a foundation for discussion and consideration for patients with VVA.

The most recent meta-analysis involving 3,898,376 participants and 87,845 cases of breast cancer demonstrated increased risk of developing breast cancer for women currently using estrogen replacement therapy and estrogen plus progestin therapy (EPT).57 Overweight and obese women who took hormone replacement therapy (HRT) were at lower risk of developing breast cancer than slim HRT users and nonusers; hence, weight may be an important factor in deciding whether or not to offer HRT after breast cancer treatment.

The vaginal wall is extremely absorptive. A vaginal application of estradiol can increase blood levels 10 times higher than an equivalent oral dose.58 New research suggests that ultra-low doses of estriol (0.005%) may be effective for vaginal atrophy. In one study, women applied 1 g of either vaginal gel containing 50 mcg (0.05 mg) of estriol or placebo gel daily for 3 weeks and then 2 times a week for up to 12 weeks.59 Women using the estriol vaginal gel had a significant improvement in the vaginal maturation index and vaginal pH, while those using the placebo gel had no improvement compared with baseline.

Another study demonstrated a 7.5 mcg dose of estradiol delivered via vaginal ring was effective, as was a 10 mcg estradiol tablet inserted vaginally. These low doses did increase serum estrogen levels, but not above menopausal range of ≤20 pg/mL.60 The question is whether any increase in estrogen levels is safe, particularly for women with estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer.

Vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) also has been investigated as a possible treatment for VVA. One study divided 464 postmenopausal women with a history of breast or gynecological cancer into 3 randomized arms for a 12-week controlled trial. One arm was given vaginal applications of DHEA 3.25 mg; a second arm DHEA 6.5 mg; and the control group plain moisturizer. All 3 arms reported improvement in either vaginal dryness or dyspareunia. Neither DHEA group was statistically different from the control group at 12 weeks, but the 6.5 mg DHEA group reported significantly improved sexual health at 6 weeks.61

Of the women in this trial, 345 contributed evaluable blood, and 46 contributed evaluable cytology and pH values that facilitated further analysis.62 Circulating DHEA-S and testosterone levels increased significantly for those on vaginal DHEA in a dose-dependent manner compared to plain moisturizer. Estradiol was significantly increased in those on 6.5 mg per day DHEA but not in those on 3.25 mg per day DHEA (P<0.05 and P=0.05, respectively).

Estradiol also did not increase in participants who were on aromatase inhibitors (AIs), which makes sense when considering the steroidogenesis pathway: DHEA → androstenedione ↔ testosterone → estradiol. “Excess” DHEA can convert to testosterone, which the aromatase enzyme can then catalyze to estradiol production. If that pathway is blocked, however, as in AI therapy, testosterone cannot convert testosterone to estradiol. Maturation of vaginal cells was 100% (DHEA 3.25 mg/d), 86% (DHEA 6.5 mg/d), and 64% (plain moisturizer), suggesting that DHEA 3.25 mg is the more appropriate dose; pH decreased more in DHEA arms than with plain moisturizer.

Hormone replacement therapy vs nonhormonal lubricants and vaginal pH

Key point: both hormonal and nonhormonal lubricants will improve vaginal lubrication and maturation, but only hormonal supports will change (acidify) vaginal pH.

Nonsurgical vulvovaginal rejuvenation

Nonsurgical vulvovaginal rejuvenation is defined as “the application of thermal or nonthermal energy to vaginal tissue, stimulating collagen regeneration, contracture of elastin fibers, neovascularization, and improved vaginal lubrication.”63 Both aestheticians and gynecologists offer 2 types of nonsurgical, nonhormonal treatment for VVA: the Erbium:YAG (Er:YAG) laser and a variety of radiofrequency devices.

Carbon dioxide and Erbium:YAG laser treatments for vulvovaginal atrophy

Both CO2 and Er:YAG lasers have been evaluated for their ability to rejuvenate vaginal tissue. The Er:YAG is considered the “second generation” of thermotherapy for VVA.64 The Er:YAG laser emits light at a wavelength of 2.94 µm and is 16 times more highly absorbed by water than the CO2 laser light.65-67 Because of this higher water absorption rate, the Er:YAG causes much more superficial penetration and ablation of tissue. Most importantly, the Er:YAG laser does not increase the zone of thermal damage with each subsequent laser impact, as the CO2 laser does. Currently, the Er:YAG is the most commonly used laser treatment for VVA.

With the Er:YAG laser patients usually are treated once a month for 3 months. Women are instructed to refrain from intercourse for at least 2 weeks after treatment. Laser treatments address the vagina only, not the perineum. Published data suggests the treatments need to be repeated annually.68,69

The Er:YAG laser has demonstrated promising results for breast cancer survivors. In one study 43 postmenopausal breast cancer survivors were treated with 3 laser applications every 30 days. Their symptoms were assessed before treatment and after 1, 3, 6, 12, and 18 months, using 2 methods: subjective visual analog scale (VAS) and objective Vaginal Health Index Score (VHIS). For all of the women in the study, vaginal dryness, VAS, dyspareunia, and VHIS scores significantly improved after the third treatment. The scores declined at 12 and 18 months but were still significantly improved compared with baseline. The study suggests “vaginal erbium laser is effective and safe for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors.”68

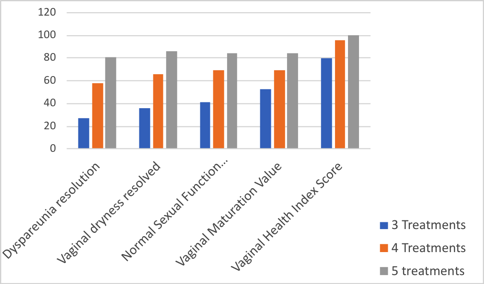

Using laser devices for VVA truly is a formative science, and we do not have definitive answers about the optimal number and frequency of treatments. Athanasiou and Pitsouni aimed to address this question in a recently published study.69 In their study, 55 women received 3 sessions of CO2 laser therapy, 53 had an additional fourth session, and 22 had an additional fifth session. Results of their study are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Improvement in sexuality-related parameters among women treated with carbon dioxide laser therapy for vulvovaginal atrophy after 3, 4, and 5 treatments.

The authors concluded that laser therapy may contribute to complete regression of dyspareunia and dryness in a dose-response manner. An additional fourth or fifth session may further increase the GSM symptom-free rate.

Radiofrequency devices for vulvovaginal rejuvenation

Radiofrequency devices are the newest options for treatment of VVA. The radiofrequency treatments include monopolar, bipolar, and multipolar devices. We have far fewer studies to corroborate their safety and effectiveness compared with laser treatments.

Radiofrequency treatments are repeated weekly to monthly, usually for a total of 3 treatments. While the CO2 and Er:YAG lasers treat only the vagina, the radiofrequency devices rejuvenate the perineum as well. Women can have intercourse the same day. Like the laser treatments, the effects of radiofrequency treatments diminish over time and likely need to be repeated annually.70

Summary of nonsurgical treatment for vulvovaginal atrophy

Both the laser and radiofrequency treatments offer viable options for nonhormonal treatment of VVA. The CO2 and Er:YAG lasers have been used clinically for a couple of decades, while the radiofrequency devices offer promising new treatment options. The Er:YAG laser has been shown to benefit both VVA and mild to moderate stress urinary incontinence (SUI).71 Less is known about the effectiveness of the radiofrequency devices for treating SUI, but they have the added benefit of treating the perineum as well as vaginal tissue. Insurance companies do not currently cover either laser or radiofrequency treatments for VVA or SUI, and the out-of-pocket expenses are customarily $1,000 per treatment.

Sexual Changes For Men After Cancer

The primary sexual concerns men report after cancer treatments are ED, surgical sequelae, and age-related changes.6

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non–skin cancer for men, and treatments can have a devastating effect on sexuality. The Fourth International Consultation for Sexual Medicine (ICSM 2015) made the following recommendations for healthcare practitioners working with prostate cancer patients:

- Healthcare providers should discuss the potential for postsurgical ED, temporary or permanent, with every candidate for radical prostatectomy (RP).

- Men undergoing RP are at risk of sexual changes other than ED, including the following:

- Decreased libido

- Changes in orgasm

- Anejaculation

- Peyronie-like disease

- Changes in penile size

- No conclusive evidence supports any specific surgical technique (eg, open vs laparoscopic vs robot-assisted RP) as promoting better postoperative erectile function (EF) recovery results.

- Data are inadequate to support any specific regimen as optimal for penile rehabilitation.

- Recovery of postoperative EF can take several years.

- Recognized predictors of EF recovery include but are not limited to younger age, preoperative EF, and bilateral nerve-sparing surgery.

Impacts of prostatectomy and radiotherapy treatments

Prostate cancer patients often undergo either RP or radiotherapy but may not be given information about the possible outcomes of these treatments. At 2 and 5 years posttreatment, patients who have RP are more likely to have urinary incontinence and ED and less likely to have bowel urgency than those who have radiotherapy. At 15 years, however, there is no significant difference in sequelae between the 2 treatment groups.72

In the short term (2-5 years), patients are choosing between urinary incontinence and ED or bowel urgency. While both treatments involve challenging side effects, having this information allows a patient to make informed choices that can significantly impact his lifestyle. A late-stage prostate cancer patient with a poor prognosis for whom sexual life is very important, for example, may choose treatment that preserves his EF. For an earlier stage prostate cancer patient who has a good long-term prognosis and wishes to continue traveling, choosing RP may be more appropriate so that he can avoid bowel urgency.

Another major decision facing RP patients is whether and when to have salvage radiation therapy (SRP). Erectile recovery after nerve-sparing surgery takes 18 to 24 months.73 However, 3 recent studies (Southwest Oncology Group [SWOG], European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer [EROTC], and a German study), all suggest the optimal time for radiation salvage treatment is within a month of RP surgery.74-76 This creates a very difficult balance between protecting healing time after RP to optimize sexual function and initiating radiation therapy for maximum benefit.

Factors that predict greater success with salvage radiation include the following:77

- Gleason’s score of >8

- Pre-radiation therapy prostate-specific antigen (PSA) of >2.0 ng/mL

- Positive surgical margins

- When treatment was given for early recurrence (PSA level ≥2.0 ng/mL), patients with Gleason scores of 4 to 7 and a rapid PSA doubling time (PSADT) had a 4-year progression-free probability (PFP) of 64% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 51%-76%) and 22% (95% CI: 6%-38%) when the surgical margins were positive and negative, respectively. Note that the patients with positive surgical margins had a better PFP (64%) than those with negative margins (22%).

- Pretreatment PSADT of >10 months

- No seminal vesicle invasion

Patients with all 5 features had a greater than 70% chance of biochemical control 4 years after SRP.78

Researchers have relied primarily on retrospective studies to determine the efficacy of adjuvant radiation therapy (ART) and SRT. Three prospective studies currently are underway, comparing ART vs early salvage: RADICALS (NCT00541047), RAVES (NCT00860652), and GETUG 17 (NCT00667069). These trials have comparable designs and recruited men with high-risk disease at RP with a postoperative PSA <0.2 ng/mL. Men in the control arm all receive prompt SRT in the event of rising PSA, which was a weakness in the 3 retrospective studies. Researchers plan to pool analyses of these 3 trials for a total of more than 1,200 patients to help determine the role of ART.79

Three lines of therapy for erectile dysfunction

Conventional medicine offers 3 lines of therapy to address EF for noncancer patients:

- First line: phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5) therapy

- Second line: vacuum constriction devices, intraurethral prostaglandins, and penile injection therapy

- Third line: penile prosthesis implantation

Combining these therapies often yields better outcomes for cancer patients.

First line: phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor therapy

Originally developed by Peter Dunn and Albert Wood for angina and hypertension, PDE5 drugs had the unexpected, and extremely lucrative, side effect of changing EF. The PDE5 drug class now includes 5 drugs that vary primarily in the speed and duration of their effect. Although PDE5 drugs are a first-line therapy, some cancer patients, particularly late-stage patients, are not good candidates for this treatment. The PDE5 drugs are strong cytochrome P-450(CYP)3A4 pathway metabolizers and have a more minor impact on CYP2C and CYP3A5 pathways, all of which can interfere with chemotherapy and immune therapy drugs. In addition, these drugs are not recommended for patients with renal and/or hepatic impairment, fairly common conditions with late-stage cancer patients. Insurance companies may not cover the cost of PDE5 drugs for ED, and a single pill can cost up to $22.49, making this therapy cost-prohibitive.

L-arginine, saw palmetto, and Pycnogenol for erectile dysfunction

Supplementing L-arginine and Pycnogenol may offer support for ED.80 In one study, 40 men ages 25 to 45 with mild ED were given 1.7 g L-arginine per day for 1 month. At the end of the month, 5% of the men experienced normal erections. During the second month, study participants added 80 mg Pycnogenol to the L-arginine. At the end of the second month, 80% achieved normal EF. During the third month, study participants continued L-arginine and increased Pycnogenol to 120 mg, and 92.5% achieved normal EF.

Participants in this study were relatively young in comparison with the average age of 66 for prostate cancer diagnoses.81 The improvements during the second and third months may have been a result of prolonged L-arginine therapy rather than the addition of Pycnogenol. Another study compared the effects of taking 320 mg of saw palmetto (n=19) with supplementing a combination of 368 mg aspartate, 460 mg L-arginine, and 80 mg Pycnogenol (n=20). Both groups showed improvement in International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and IPSS-QOL. The Pycnogenol, arginine, and aspartate group also showed improvements in Overactive Bladder Symptom Score (OABSS) and International Index of Erectile Function 5 (IIEF-5). Neither group showed changes in incontinence or uroflowmetry.82

A study comparing L-arginine and L-citrulline levels in controls and patients with ED found a significant proportion of ED patients had low L-arginine or L-citrulline levels, particularly patients with arteriogenic etiology of ED.83 The study demonstrated that oral L-citrulline supplementation increases serum L-arginine levels more efficiently than L-arginine by itself, which in turn increases nitric oxide (NO) production.84

Contraindications for L-arginine supplementation

Despite the benefits of L-arginine therapy for ED, recent research suggests cancer therapies that reduce arginine levels promote prostate cancer autophagy and cell death.85,86 Because L-arginine increases NO and therefore blood flow, albeit for a very short duration, L-arginine may potentiate prostate cancer growth. The bottom line: use L-arginine and other NO-promoting amino acids with caution for prostate cancer patients.

Second-line therapies: vacuum erectile devices and penile injection therapy

Fibrotic changes following RP can be prevented by increasing oxygenation of the corpora. Vacuum erectile devices (VEDs) can be used daily for 5 to 10 minutes without the constriction ring to maximize venous flow and oxygenation. The constriction ring prevents venous outflow, thereby reducing the percentage of oxygenated blood and resulting in ischemia after 30 minutes. Vacuum erectile devices are an excellent treatment option after RP surgery because they can stimulate oxygenation of the corpora without the need for an intact nerve supply. Increasing oxygenated blood flow may reduce or even reverse fibrotic changes after RP.87

Studies demonstrate that a VED used for 5 to 10 minutes per day in combination with the PDE5 drug tadalafil taken 3 times a week has a success rate of 90% as measured by the IIEF-5 at 1 year. In comparison, RP patients taking tadalafil alone, without using the VED, had a 60% success rate.88 The combination of VEDs with the PDE5 drug sildenafil after RP surgery resulted in 30% of the men reporting a return of spontaneous erections.89 In summary, VEDs can enhance the effectiveness of other ED therapies.

Penile injection therapy

In France, the primary sexual rehabilitation treatment is intracavernous alprostadil injections (IAI). The French healthcare system, financed by government national health insurance, will pay for IAI therapy but not for PDE5 drugs. Several studies demonstrate EF improves with early and regular IAI alone and/or in combination with other therapies.

A French study examined the effectiveness of IAI injections beginning 1 month after surgery.90 Patients learned how to administer their own twice-weekly injections and continued the treatment for a year. They were encouraged to have intercourse as often as possible. One segment of the study group continued injections for another year, but they experienced no more improvement after the first year. Study participants who continued treatment beyond 12 months reported an increase in penile pain, and 30.6% of the patients reported worsened erection at 24 months compared with 12 months.

In the United Kingdom, the annual cost for VED plus PDE5 therapy is approximately US $349, with an 80% compliance rate. In contrast, the annual cost of penile injection therapy is approximately US $1,533 per year, with only a 40% compliance rate.

Third-line therapy: 3-piece inflatable devices

Penile implants offer flaccidity and erection that approach natural function. Design improvements in the last 5 years have reduced mechanical failures, resulting in a 92% to 94% success rate. These newer implants have antibiotic and hydrophilic coatings that have significantly reduced infection rates. The primary risks with penile implants are infection and penis shortening.91

Men can enhance recovery from implant surgery by inflating the penile implant daily for the first 6 months. After that time, 6 to 12 months post-surgery, patients ideally would inflate to maximum for 60 to 120 minutes each day. Following this protocol, some men have an increase in penile size at 6 months and 12 months.98

Revitalizing Sexual Health

When patients request help with increasing libido, restoring their core vitality is helpful so that they have enough energy to “over-spill” into their genital organs. Although reproduction is essential for our survival as a species, the genital organs are not essential for our personal survival. For example, 91% of 738 young females studying health sciences reported menstrual problems including irregular menstruation (27%), abnormal vaginal bleeding (9.3%), amenorrhea (9.2%), menorrhagia (3.4%), dysmenorrhea (89.7%), and premenstrual symptoms (46.7%). Researchers found a significant positive correlation between high perceived stress and menstrual problems,92 suggesting that the body places its attention first on the vital organs, that is, the heart, lungs, intestines, and liver, before sharing vitality with the reproductive organs.

Frequency of intercourse

Personal and cultural expectations about sexuality can strongly impact a patient’s distress about libido. Classical medical systems, including Chinese medicine, aim for a balance between too little and too much sexual activity. The table below represents a summary from the classic Chinese text, the Su Nei Jing (Table).

Table. Chinese Medicine Guidelines for Frequency of Intercoursea

| Age (y) | Minimum | Average Health | Good Health |

| 20+ | Every 4 days | Once a day | Twice a day |

| 30+ | Every 8 days | Every other day | Once a day |

| 40+ | Every 16 days | Every 4 days | Every 3 days |

| 50+ | Every 21 days | Every 10 days | Every 5 days |

| 60+ | Every 30 days | Every 20 days | Every 10 days |

aAdapted from Wood E, 2015.93

Integrative practitioners have a wide variety of therapies that can enhance core vitality. Improving nutrition, for example, can profoundly increase a patient’s vitality. The Mediterranean diet in particular has been shown to improve ED.94 Late-stage cancer patients may not be able to engage in strenuous physical activity, but restorative exercise such as yoga, qigong, and tai chi could be very beneficial. Improving the quality and length of sleep reduces risk of several types of cancer95-97 and increases energy reserves for fueling libido.

Intercourse and chronic illness: Traditional Chinese Medicine perspective

Much of the discussion to this point has supported intercourse and intimacy during cancer treatment and survivorship. While Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) supports physical intimacy with a partner, intercourse is discouraged. From a TCM perspective, ejaculation for men and vaginal lubrication for women expend “jing,” the vitality inherited from our ancestors, as well as qi. During late-stage disease, these energy sources ideally are reserved for healing and restoration.

The Japanese practice of “Karezza”98 encourages sexual penetration followed by relaxation and intimate touching, without progressing to orgasm. Taoist sexual practices focus on raising sexual energy and then directing it into the internal organs for rejuvenation. Both practices focus sexual energy inward for revitalization, rather than “spending” the energy through orgasm.99,100

Enhancing intimacy for cancer patients

Cancer patients and others with late-stage, chronic diseases can enhance intimacy by planning ahead. Encourage patients to set dates and start “making love” 3 days beforehand; for example, leaving notes for each other, spending more time talking intimately, and cuddling. The dates might be scheduled early in the day, when a patient’s energy level is higher. Patients may clear out other appointments and even nap to save energy for that special time with their partner. Holding hands increases intimacy, as does emotionally vulnerable conversation. During the date, let go of the expectation that intimacy will lead to intercourse. Aim to be in the moment as much as possible, enjoying each other’s company.

Sex therapist Jane Guyn, PhD, RN, recommends the 5 most erotic things you can do with your mouth: kissing, licking, biting, sucking, and talking. “The fifth one is actually the most important,” says Guyn. “When you talk to your partner about what is true for you, you can create something that is absolutely fantastic.”101

Summary

Cancer alters almost every aspect of patients’ and caregivers’ lives, including their sexuality. Patients look to their healthcare providers to start the conversation about sexuality. Many patients never receive information about how cancer treatments may affect their sexuality. You can be a vital resource for filling those information gaps. Sexuality is much more than intercourse. You can help patients and their partners expand their understanding of intimacy and sexuality to include all aspects of sensuality. Remember that LGBTQ patients and their partners require appropriate support, both during and after cancer treatment. Sexuality has a place in end-of-life care and can profoundly enhance a patient and their partner’s last phase of life together. Naturopathic and other vitalistic medicines offer tools to restore core energy, which in turn can enhance libido and sexuality.